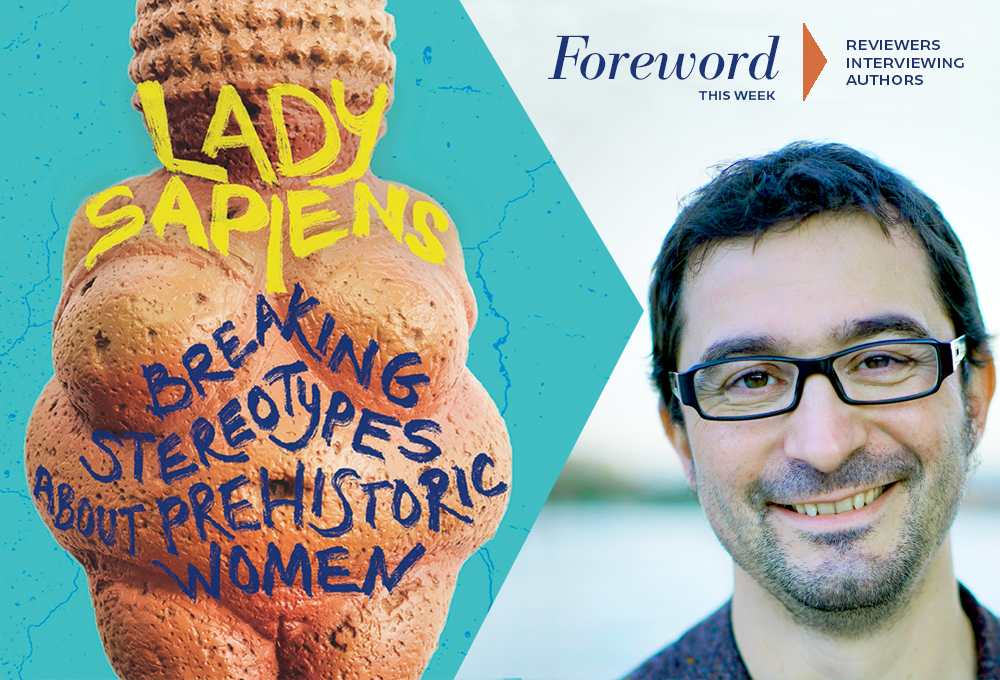

Reviewer Jeana Jorgensen Interviews Thomas Cirotteau, Author of Lady Sapiens

It doesn’t take much in the way of misogyny to get our dander up, but we’re especially sensitive to abuse that is based on the notion that women are the weaker sex—physically, intellectually, emotionally, or otherwise. Much of that hogwash was and is perpetuated by religion, of course, beginning with the damaging and wrongful use of he/him when referring to God. But human society is so run through with sexist dogma we’d be best served by just starting over.

Be that as it may, while preparing for Foreword’s March/April issue, we were thrilled to discover Lady Sapiens, which “corrects mistaken stereotypes about prehistory, asserting the primacy of women in past societies and honoring the foremothers who advanced civilization with their art, knowledge, and power,” in the words of reviewer Jeana Jorgensen. “In reality,” she notes, “early women were hunters and gatherers, shamans and healers, artisans and leaders,” right alongside their male companions.

Enjoy the interview.

The entire book warns against applying modern Western gender norms to ancient peoples. This is especially evident in the stereotype about “man as hunter, woman as gatherer.” Why do you think these stereotypes remain so prevalent?

I am not a sociologist and I have not studied all aspects of your question. However, it seems to me that our Western society in which we live still has a lot of progress to make in order to give women their rightful place in many areas. We are the product of our past, and it has put men in the limelight most of the time while forgetting about women. But fortunately, this society can and must change. If you allow me a personal anecdote, I have the great fortune to have two daughters who are teenagers. They often complain about the sexist remarks they receive or hear in their school lives. There is a considerable challenge to make the younger generations, boys but also girls, understand that being a woman does not force you to accept all these stereotypes.

As part of my PhD minor in gender studies, I took a course with a feminist archaeologist titled Ancient Women. In it, we learned about how difficult sexing skeletons really is (which, again, I don’t think is known by the general public). What do you think is the most significant recent advancement in this area, and why?

The traditional method is to take measurements on the bones. But this is very unreliable. The most striking example that we develop in the book and in the documentary is the Lady of Cavillon, who for more than a century was described as a man. It was during the study of her skeleton, at the end of the last century, that a team of palaeoanthropologists, led by Henri de Lumley of the IPH in Paris, tried to solve this problem. They defined a method for measuring the pelvis and in particular the curvature of the hip bone. This method gives very good results, up to ninety-five percent. However, there are few fossil pelvises, as this is a bone that does not preserve well, but there are many skulls.

Since 2010 and the analysis of the DNA of the cell nucleus, it is possible to sex fossils without mistake. But this method is destructive and it is generally very difficult to find genetic information beyond 100,000 years. In 2019, a team of researchers from the University of Toulouse, led by José Braga, discovered that the shape of the cochlea, an organ of the inner ear that allows us to hear, makes it possible to sex the skulls with ninety-five percent acuity. This method is non-destructive and non-invasive. It is not limited in time either. It is now possible to sex fossils that are several millions years old!

The section on ancient contraceptive methods was quite fascinating, especially in light of how folk methods of contraception (from using the rhythm method of tracking one’s menses and times of fertility, to various types of douches) are still prevalent in modern-day cultures. Do you think that we can draw any conclusions about what kinds of cultural values might be evident in the types of birth control methods that are available and preferred, in cultures from any time period?

I’m sorry, but I don’t understand your question. During our investigation we were careful to avoid any generalisation. The women of the Upper Paleolithic are plural and probably very different depending on the place and the time. Through Lady Sapiens, we wanted to highlight all their potential. While we have drawn parallels between present-day hunter-gatherer societies and those of the Upper Paleolithic, we do not believe that they are identical. We can say very little about prehistoric cultures and the thinking of Upper Paleolithic humans, their ways of seeing the world, of representing it.

At the end of the first chapter, you caution readers against assuming that anthropological findings about contemporary hunter-gatherer cultures could be uncritically applied to ancient cultures. Can you expand a little on why this is a fallacy to be avoided?

As I point out, it is very difficult to know the thinking of humans in the Upper Paleolithic who lived in an environment very different from our present world. Today’s hunter-gatherers have exchanges with our “modern” societies. Nor are they the direct descendants of prehistoric societies. They also may have been sedentary in the past before becoming nomads. Their ways of thinking may therefore have evolved throughout their history and their exchanges. As Sophie Archambault de Beaune points out, it is however possible to create technological parallels. Today we know prehistoric ecosystems fairly well. A present-day human group in a similar ecosystem may have developed technical or technological solutions identical to those of prehistoric societies.

Why do you think the Venus figurines continue to capture the fascination of both scholars and the general public?

These Venuses fascinate the general public because they are among the few human representations we have from the Upper Palaeolithic. In addition, their very pronounced silhouette with its wide hips, rounded buttocks, and heavy breasts never ceases to puzzle scientists. Why did the Sapiens of 30,000 years ago choose to represent these women in this way? Did this correspond to the aesthetic canons of the time or should we see a strong symbolic dimension referring to the power of childbirth? These questions are still being debated, but they do not detract from the visual strength of these representations and their evocative power.

The premise that post-menopausal women were actually quite important to everyday life and the ability of those in the group to both survive and thrive is intriguing, given that you note that in non-human primates, these females can be neglected and isolated. And in many modern Western cultures, the status of women declines as they age out of reproductive years and shift out of beauty ideals that are biased towards youth. Is it possible that our ancestors were more egalitarian-minded than some modern folks? Or does this kind of analogy not even really work in the first place?

Prehistoric archaeology tells us that human groups from the Upper Paleolithic and even earlier took care of their elderly and/or sick elders. From 1.8 million years ago in Dmanissi, Georgia, the toothless skull of a homo erectus bears witness to this behaviour, which continued throughout the Paleolithic. Were these human groups egalitarian? I don’t think that this modern concept can be modelled on prehistoric societies. Especially since it is not only defined by the care we give to the elderly.

How does readjusting the narrative about prehistoric women impact ideas about women and gender today?

I won’t talk about gender, which is the expression of masculine and feminine. We have no idea of this in the prehistoric societies of the Paleolithic. On the other hand, it seems essential to me to reveal the rightful place of women in the evolution of the human species. This history, our history, was not made solely thanks to men, as we have been told for over a century. Women have played an essential role in the advent of our species, we Homo sapiens. All generations must be aware of this today.

Are there any new developments in the field that have occurred since the book’s publication that you’re eager to share with readers?

I have not yet seen any new research on this particular topic.

Jeana Jorgensen