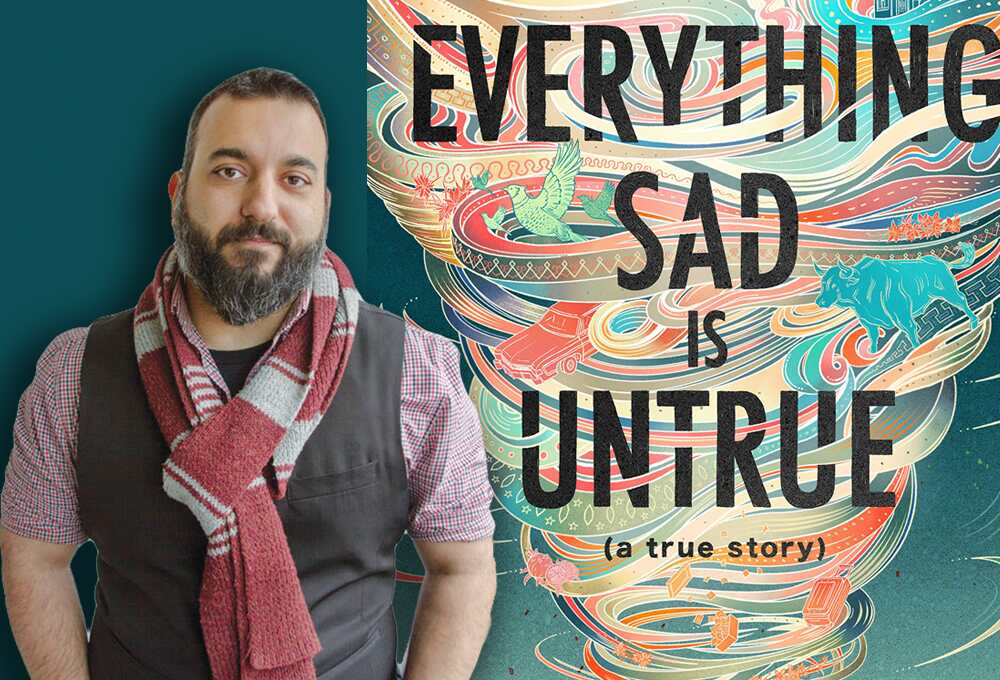

Reviewer Camille-Yvette Welsch Interviews Daniel Nayeri, Author of Everything Sad Is Untrue

Great novels appear in all shapes and guises, but is anything more heartwarming and important than a brilliant work of fiction for young readers? Never forget that we are adult readers because of books like Little House on the Prairie, Charlotte’s Web, The Giver, Harry Potter, and other gems of literature that woke us from childhood slumbers and proved that stories offer pleasures as wonderful as anything our imaginations might create. Those of us in the business of books must never forget that those magical moment happen every hour of every day to countless children.

This week, we’re thrilled to hear from Daniel Nayeri, author of Everything Sad Is Untrue, a recently released gem of juvenile literature, one that is sure to fire up a whole new batch of lifetime readers through the storytelling skills of twelve-year-old Daniel, an Iranian refugee in Oklahoma.

In her starred review for Foreword Reviews, Camille-Yvette Welsch writes that the book’s “narration is by turns wounded, hopeful, funny, and angry,” as “Daniel tries to say what he knows to be true, about everything from poop to blood to the food that people eat.” Unfortunately, his “storytelling alienates his classmates, making him even more of an outsider, unable to piece together who he is and who he wants to be.”

Yes, Everything Sad Is Untrue is an immigrant story, perfect for our times. With the help of publisher Levine Querido, we connected reviewer Camille-Yvette with author Daniel for this delightful conversation.

In the book, young Daniel often tells the reader “A patchwork memory is the shame of a refugee.” Yet, Daniel also uses that patchwork to piece together his identity as a Persian and an American and a refugee and as a storyteller. Is there a way to do it that is without piecework? Why is shame a part of it?

That line is a central theme of the book, and came from my own sadness as I wrote it. Throughout the process, I found myself wishing I had access to family members, photos, places. I couldn’t help but think of all the ways in which I had broken the lineage of my family. Our linear history. The refugee is quite literally cut off from the orchards that a grandfather planted. There is no grandmother to teach the best methods of straining yogurt. Old teachers who might have taught the previous generation. Houses or heirlooms, even old pictures tucked in a book on a dusty shelf. These are the things I mean. The stories are cut off. There are bits of memory, phrases here and there, a passing mention of a tradition. The refugee is constantly trying to piece this all together. To make sense of one’s self as a part of the fabric. It feels shameful to be so unclaimed.

Your parents are fascinating characters who really defy stereotypes. Your mother endured domestic violence, had a fatwa on her head, but still managed to be absolutely unstoppable, and your father is an unlikely hero for xenophobic twelve year olds in Oklahoma yet he enthralls all the Americans who meet him. They are both victim and hero in many ways as is the narrator, and yet neither of those binaries quite fit. How were you able to see your own family members with such clarity and compassion?

They’re my parents, and I’ll never quite see them as individuals in their own right. But they’re perfect characters for a novel. Did you know my mom joined the Peace Corps in her late 50s and moved to Thailand? Did you know my dad once walked into a restaurant and ordered the entire left side of the menu? I don’t think either of those anecdotes made it into the book. They’re both incredibly interesting people. I suppose I just didn’t want to waste the opportunity.

You write a lot about the scatalogical in the book. Why was it so important to include that part of a kid’s reality?

Thank you for being the first to ask this question, because I have even more to say about poop. There is a scene in Midnight’s Children by Salman Rushdie where the narrator, Saleem Sinai, looks out a window and sees an old man defecating out in public.

This is after the book has discussed the image of pickling as a form of preserving memories, as writing itself. The ability to defecate is cast as the ability to create—literally to reconstitute food, pickles, as some new thing. Writing is somehow both pickling and pooping. I understand this is gross, but it might also be the best metaphor for art. Anyway, the old man laughs when he sees Sinai and says, and I’m paraphrasing, “I used to make them this big!” and he holds his hands like he’s telling a fish story. Sinai is almost wistful and connects it to storytelling.

His response is, “Once, when I was more energetic, I would have wanted to tell his life story; the hour, and his possession of an umbrella, would have been all the connections I needed to begin the process of weaving him into my life, and I have no doubt that I’d have finished by proving his indispensability to anyone who wishes to understand my life and benighted times; but now I’m disconnected, unplugged, with only epitaphs left to write.”

In my book, Khosrou, is experiencing pooping as a form of storytelling as well. When he comes to America, he doesn’t know how to do it. The conventions of Western toilets (and Western plot structure) are new, and he’s unable to produce anything. He becomes preoccupied with the nature of food in all the countries he visits, and the kind of poops they make. At one point he is immersed in a trench full of poop. Khosrou, unlike Saleem Sinai, is full of energy, and risks being overcome by the agglomeration of stories all around him. In the story, he’s asked an important question that finally helps him parse through all this. But I won’t spoil it.

Thank you for putting up with more poop talk.

What is the significance of the title Everything Sad is Untrue: (a true story)?

That phrase comes from The Lord of the Rings, when Samwise Gamgee—who is suffering through a terrible journey—sees a resurrected Gandalf and asks “Will everything sad become untrue?” I adore that question. And it resonates with the epigraph for the book, a passage from the Brothers Karamozov, that begins, “I believe like a child that suffering will be healed and made up for.”

Both sentiments are of a great future hope, proclaimed in a moment of deep anguish. In the case of Khosrou, the narrator of my book, he is certainly as much a true believer as these other two speakers. But he is also a maker of his own reality, at least, in the sense that I could easily imagine him make the logical leap that IF everything sad will become untrue one day, then it may as well be untrue today.

Your book enters the world at a crisis moment in history. What do you hope young writers glean from reading it and how does that relate to the state of the world?

George Orwell said all art is propaganda, and he’s never been more right. But he was never less right either. I think all art is an act of persuasion. All art is trying to convince us of something. Broadly speaking, that something is, “What is important?” Some might say, “What should we worship? What should we prioritize in life?” Even a coloring book is telling you to prioritize some things over others. You bought it after all. There is no neutral art. Some art is doing nothing more than trying to convince you that the artist is a genius.

So then, what does this book ask you to prioritize? What does it ask you to spend your time thinking about? I think we set up the problem in your first question. The patchwork nature of a refugee is his shame, sure. But we are all ashamed, I think, because we feel unloveable. And, as in the book, we all want loving hands to hold our faces and tell us we are good. What would it mean if we all saw ourselves as refugees, claimed into a love like that?

I think at the very least, it would mean we would welcome outsiders in. And maybe we’d even go outside to meet them.

Camille-Yvette Welsch