Is There a Right Way to Remember 9/11?

Fifteen years after the fact, the events of September 11, 2001 are still not simple to reckon with. This is true for anyone old enough to remember that day, but it is a reality even more fraught for those who lost family members in the attack. Jay Aronson’s new book, Who Owns the Dead? (Harvard University Press), takes an incisive and nuanced look at how memorialization played out in New York City, particularly in relationship to the wants and needs of surviving family members.

While 9/11 books are plentiful, this may be the first to honor the varied voices of those left behind—who waited, or who are still waiting, to hear if any traces of their loved ones were found; who fought hard to make sure that the remnants of the towers were treated with respect. Who Owns the Dead? is both a meticulous and illuminating look at how the victims of national disasters are honored on a massive scale, and at how complicated the task of public memory is. We asked Aronson about his research and writing.

When and why did you decide to tackle this very weighted topic?

Jay Aronson, Harvard University Press. 'My first goal was to say something new about 9/11 that gave Americans insight...and hopefully empathy.'

The World Trade Center story was initially just one of many case studies in a grant that I had received from the U.S. National Institutes of Health to study the ethical and political dimensions of identifying the missing after conflict and disaster. I had previously examined how DNA identification was changing our legal understanding of the right to post-conviction remedy in the American criminal justice system, and broadening the scope of rights I was studying, and the geographic reach of my work, was a logical next step.

I was initially quite reluctant to delve too deeply into issues relating to September 11, both because they were so politically contentious and discussed far too often in popular media and popular culture. The result, I thought, was a dumbing down of American discourse around the risks of terrorism and an overwhelming fear that we would be attacked again. Also, I naively thought that the World Trade Center recovery and identification effort was the kind of success story that would serve as a model for other countries, where the lack of political will and resources to engage in identification and memorialization made the process more challenging. That turned out to be a terrible assumption!

My initial plan for this case study was to write two scholarly articles about controversies surrounding the use of Fresh Kills landfill on Staten Island as the staging ground for sifting of materials from the World Trade Center site, as well as disagreements about the internment of remains in the Memorial Museum Complex. The more I read about those two issues, the more I realized that I needed to understand the entire story before either of them would make sense. The views of dissenting families, who play a crucial role in my narrative, just didn’t make sense. So, in essence, I decided to go back to the beginning of the story, and it very quickly became clear to me that this had to become a book length study. Once I made this decision, my first goal was to say something new about 9/11 that gave Americans insight both into an epochal moment in our history and hopefully empathy for the kinds of mass atrocity situations that other people face around the world on an all-to-frequent basis, often partly a result of our own foreign policy choices.

You reference a lot of 9/11 literature—both fiction and nonfiction—throughout your book. Other than Who Owns the Dead?, which titles would you consider particularly crucial reading for understanding that day and its aftermath?

For starters, I think the most important works on the subject are those that allow the people involved to tell their own stories. Damon DiMarco’s Tower Stories is a particularly good example of this genre, as is Dennis Smith’s Report from Ground Zero. Jim Dwyer and Kevin Flynn’s 102 Minutes: The Untold Story of the Fight to Survive Inside the Twin Towers does a great job of explaining what it was like for the people struggling to evacuate the towers after the attacks.

The best book I’ve read lately on the subject is actually a work of fiction: New York Times reporter Amy Waldman’s 2011 novel The Submission, which imagines what would have happened if the winner of the memorial design competition was Muslim. Cloaked in the veil of fiction, she was able to explore the personalities involved in the memorialization effort in a way that one cannot examine them in serious journalistic or academic contexts. She was able to delve into her characters’ psyches and complex motivations for engaging with September 11 in a way that rang true to me. I should note that I only read this book after my own work was published, because I did not want the fictional account to have an impact on my telling of the story.

I am also looking forward to finally reading Don DeLillo’s Falling Man, Jonathan Safran Foer’s Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close, and Colum McCann’s Let the Great World Spin.

There are so many great academic works on related topics that I feel obligated to at least mention the names of people who most influenced me: Ed Linenthal, Tom Laqueur, Adam Rosenblatt, Paul Goldberger, Katherine Verdery, and Sarah Wagner among many others. I could go on and on, but I’ll stop for the sake of space and just tell readers to take a look at my footnotes.

Can you tell us a little about the process of working with Harvard to bring Who Owns the Dead? to print?

Working with Harvard University press was a great experience overall. I brought the project to my first editor Elizabeth Knoll on a trip to Cambridge in Summer 2013 just to get feedback from her and advice on how I might submit it to the press. To my great surprise, she was very enthusiastic about the project and essentially agreed to take it on right then and there. I was honestly quite surprised by her reaction, mostly because I was not particularly confident in the project yet. At the same time, I was excited that a press like HUP was willing to work with me on the book and happy not to have to shop it around to other publishers.

Once we had worked out a contractual arrangement, she gave me one round of comments and corrections, most importantly about honing my authorial voice, but then left the press to take on an administrative role within Harvard University. I was initially concerned about switching editors midway through the writing process, but my new editor, Andrew Kinney, did an amazing job of taking it over and shepherding it through the editorial process. He was particularly good in helping me massage my academic prose into writing that was more suitable for a broad audience without losing any nuance. I also got incredible feedback from one of the peer reviewers and several friends and colleagues, which allowed me to dramatically improve my introduction and conclusion.

All in all, I think the final product is infinitely better than the first draft, which is what the editorial process ought to be about! As far as the production process goes, Harvard and its contractors were top notch. They were efficient, helpful, and ultimately created a book that does the topic justice. I really don’t have much to say about that aspect of the process because it was so painless and uneventful.

Why did you elect to begin your book, which concerns itself largely with the “political and emotional battles” around public mourning, with a very vivid account of the attacks themselves?

The only way to understand the recovery effort and everything that came after is to understand the shear magnitude of disaster at the site. This wasn’t just a plane crash or a building collapse, it was the implosion and complete destruction of what can be thought of a small city in and of itself in the middle of one of the most important megacities in the world.

How does your research impact your personal response to, or experience of, the 9/11 Memorial and Museum?

I know so much (too much!!) about the behind-the-scenes battles and political dysfunction surrounding the design and construction of the memorial and museum that it was nearly impossible for me to experience it objectively. Further, I had made it my job to explain the objections that some family members had to aspects of the design and focus of both in a rational way, and in doing so, I obviously came to empathize with them and their perspective.

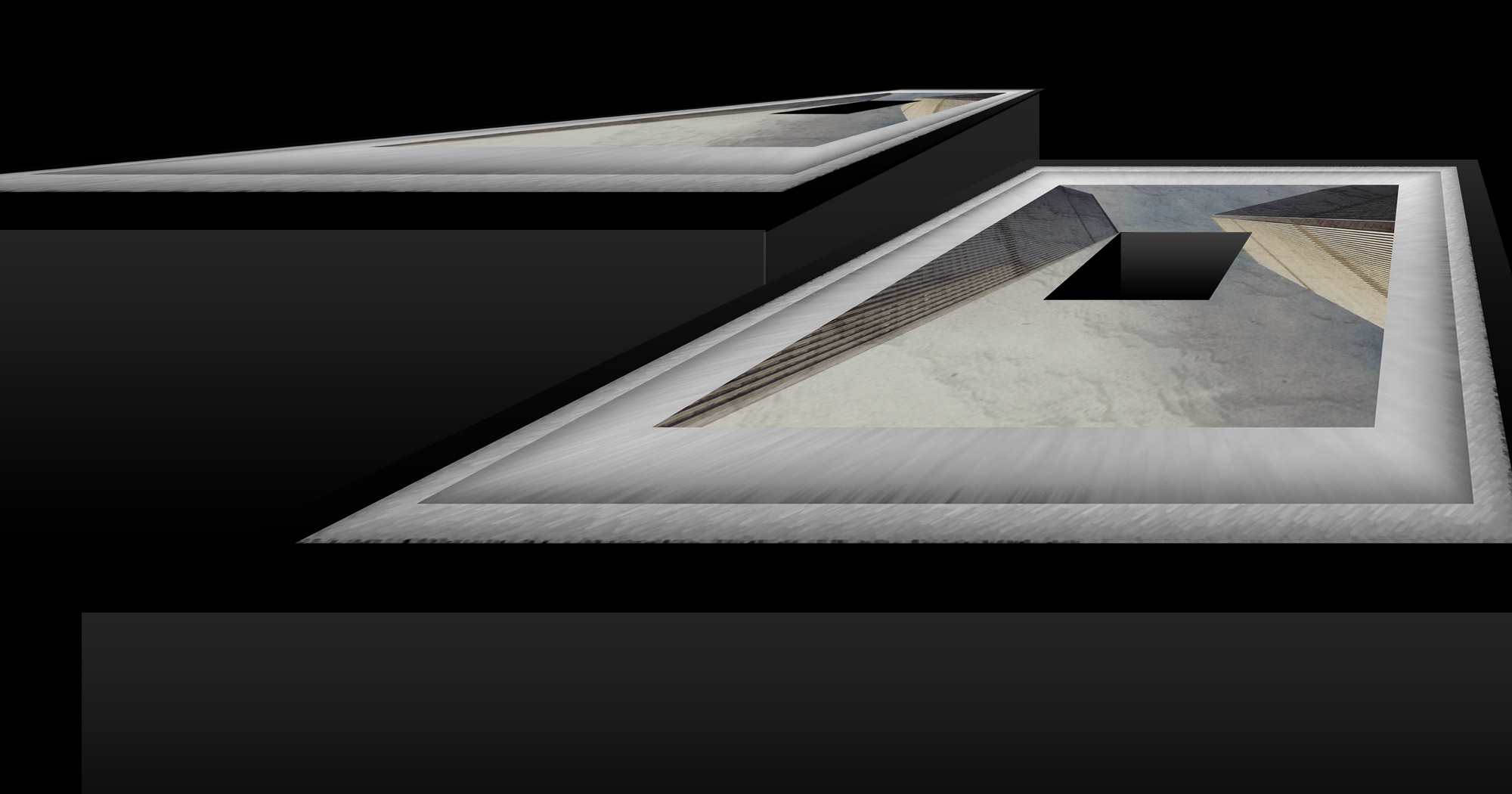

At the end of the day, though, I think the memorial and museum both do a nice job of accomplishing their goals in a dignified and respectful manner. I particularly like the design of the exhibits in the museum and have spent many, many hours there lingering over small details of the most mundane objects. In fact, it took me two multi-hour visits just to make it all the way through the museum displays for the first time. My biggest complaint about the complex is the cost of entry and the almost airport-like security regime that they have enacted. I understand that it could itself become a potential target of terrorism, but I, like some other critics, feel that the security experience could be used in a more meaningful and pedagogical manner.

Your project focuses mostly on memorialization, and the battles around it, in New York City. Did similar struggles occur at the other sites that were hit that day?

Battles about recovery from conflict and disaster, and disputes over how to best memorialize the victims, occur all over the world in response to tragedy because resources are at stake and memory and political legitimacy are on the line.

The two other sites that were directly affected on September 11 were radically different from the World Trade Center (in one case a field in rural Pennsylvania, and in the other case a government building near Washington, DC), so the stakes were different and there were fewer stakeholders to appease. In the case of Shanksville, there was no need to rebuild a densely populated urban infrastructure, and in the case of the Pentagon, only a portion of the building was destroyed and there was no real question that anything other than restoration of the structure would take place.

The true challenge of the World Trade Center was that it was not just a mass atrocity site, but also a densely populated neighborhood were people lived and worked, a symbol of American financial might in the age of global capitalism, a key link in New York’s transportation infrastructure, and place of great historical importance in American and world history. All of those things had to be taken into account in the recovery and reconstruction process in a way that they didn’t at the other two sites.

Where were you that day? How did your experiences of the events of 9/11 inform this book?

I was in London that day doing research for my dissertation, which focused on the scientific and legal development of DNA profiling. I had just gotten back to the house of relatives where I was staying after a very productive meeting with a defense lawyer involved in challenges to the technique in England. My girlfriend (now my wife) phoned me crying to tell me that America was under attack and that planes had flown into the twin towers and now they were on fire and they might fall down. I honestly thought she had had some sort of very uncharacteristic nervous breakdown and was wondering how I was going to get her help.

I turned on the television to see what could have triggered her fear, and witnessed the collapse of the South Tower either in real time or just after it happened (I can’t remember). I was obviously in shock and spent the rest of the night on the phone with my wife glued to the television. I don’t remember the details of my remaining time in England, but I do remember going to a public vigil for the victims the next day, and that people were very kind to me when they heard my American accent.

It took me several days to get a flight back to the United States (I think I was due to return on the 13th), and one of my most vivid memories of my life was flying over New York on my way back to Boston (from Charlotte or Raleigh-Durham, again I can’t remember the details) and seeing plumes of smoke still rising from the World Trade Center site. At the time I had no idea that I would ever write a book about the attacks, but that image still sticks with me to this very day.

Michelle Anne Schingler is deputy editor at Foreword Reviews. You can follow her on Twitter @mschingler or e-mail her at mschingler@forewordreviews.com.

Michelle Anne Schingler