Diversity Includes Disability; Anthology Focuses on the 'Crippled and Naked'

Many readers and writers are focused now on how Americans can heal divides between us, and about the role that literature can play in doing so. It is also clear that hunger for unity does not mean a hunger for uniformity. Rather the opposite. Readers and writers have been pushing for diversity and may be now more so than ever.

Sheila Black: 'Disability is like sexuality. It's a spectrum.'

John Byrd, marketing director and CFO at Cinco Puntos Press, recognized this moment long before November 8. “Readership is not declining,” Bird said. “Readership for books that have this sameness is declining. If you look beyond that, there is room to reach new readers who are on the lookout for a new literature that reflects the America we live in.” With that in mind, the family-owned, Texas-based Cinco Puntos Press has sought authors and projects that might not normally be picked up by the mainstream, New York presses.

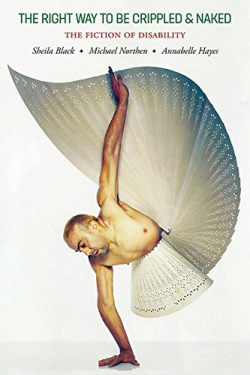

One of Cinco Puntos Press’s upcoming releases, The Right Way to Be Crippled and Naked: The Fiction of Disability: An Anthology fills a void that Byrd and co-editors Sheila Black, Annabelle Hayse, and Michael Northen recognized—an anthology of finely crafted short fiction that represents the experiences of writers with disabilities.

“The need for The Right Way to Be Crippled and Naked would seem obvious: that America’s largest and most permeable minority should receive representation on the bookshelves of the country,” writes Northen in the Afterword. “The stereotypes and negative attitudes towards disability that have accreted through our literary history and helped to form public perceptions can only be authentically transformed by moving marginalized voices to the center.”

Importantly, the “voices” and “experiences” represented here are plural. The perspectives of writers with disabilities are not monolithic, nor is there one way to write from those perspectives. The collection provides a counter to “the Trump mentality,” which “tries to reduce people in all of their complex variety to labels so that they can be easily dismissed or ridiculed,” as Northen puts it. “Our anthology is extremely diverse. The contributors wouldn’t necessarily see eye-to-eye,” says Northen.

For example, the editors note that writers and readers might have divergent views about the title of the collection, which comes from a story by Jonathan Mack. The protagonist, who describes himself as a “white, American, middle-aged, homosexual, crippled, promiscuous [person] whose life has been rife with the sort of regrettable incident,” explains his “recent decision to become a Jain monk of the Digambara (or “sky-clad”) sect.”

“It’s not that everything you write is going to be about that, but everything you write is going to be imbued with that experience,” said co-editor Sheila Black, a poet who has written about her own experiences of living with disabilities (including recently in a column for the New York Times). “Some [writers] are interested in the narrative of disability and directly address it in their work. Some are not.”

Disability is a Spectrum

Black also emphasizes that the ways people experience disability are very different. “Disability is like sexuality. It’s a spectrum,” she says. This diversity of experience is reflected in the stories, which include characters who have Alzheimer’s disease, cancer, and diabetes.

What the writers in this collection have in common is that they are committed to their art. The stories represent a wide range of what writers of modern fiction can do. Following each is a brief afterword in which the author describes their inspiration and approach to the piece. The afterwords themselves represent a wide range of styles and perspectives, but some themes do emerge from the collection. For one, although is not prescriptive or didactic, “The literature is corrective,” says Northen, in that it diverges from the “Tiny Tim” narrative and other clichés.

Noria Jablonski writes that her story, “Solo in the Spotlight,” is “an imagined version of [a quadriplegic woman’s] childhood told from her point of view—a story of an ordinary girl with ordinary longings—a kind of antidote to the so-called ‘true life’ pamphlets that sensationalized the lives of people with extraordinary bodies.” In Robert Fagan’s meta-narrative, “Census,” writerly craftsmanship is both subject and mode. His narrator calls up Borges and Joyce, stumbling around a “labyrinthine” studio. “Fall, what a fearful metaphorical use of an already frightening verb,” the narrator muses, “Falling, not having to parade words into meaning, world into shape, myself into self, but swirling among the forgotten or the dead.”

“A lot of the writers in this anthology are in their stories trying to say something about how a person with disability’s identity is constructed,” says Black. In Stephen Kuusisto’s “Plato, Again,” a woman goes from being a valued employee to an office pariah when she returns to work after having a mastectomy. “The protagonist never has a chance because her humanity is stigmatized as a matter of course,” writes Kuusisto in his afterword. The forces of ableism, sexism, and racism are in some ways are stronger than any one of the characters in the story, Black observes.

Yet these forces must be reckoned with, and the stories in this anthology are inviting and insightful opportunities to begin that work. “[One can] look at disability as an experience that gives you different insights that are unique and valuable,” says Black. “I think it’s especially valuable right now. We’re living in in a time with tremendous amounts of division and a lot of that is about value judgments that people make about other people.”

Hope for Younger Readers

We’re also suffering from the judgments that we make against ourselves. Among the editors’ biggest hopes for the book is that it will reach younger audiences. Northen points out that it could be a great tool for teachers and professors who are looking to diversify their students’ reading lists. “More exposure to disability thought could really teach people that experience has its own integrity and value. We sort of know that instinctively but we don’t have much social practice in our society that affirms that, especially [for] young people,” says Black.

One takeaway from the anthology is how much of the nation’s collective pain may be self-inflicted, because of our failure to see the beauty of diverse experiences.

Jonathan Mack’s protagonist says in the title story, “I remember I believed all my problems would be solved, if only I were beautiful. Then I was beautiful. Sorry you missed it. Actually, I sort of missed it, too.”

Emily Avery-Miller is a writer and teacher in Boston. Her prose and reviews have appeared in Bird’s Thumb, Literary Bohemian, Art New England and others. @EBAverymiller

Emily Avery-Miller