Bob Dylan's Destiny is About Change

On December 10, the winners of the 2016 Nobel Prize—among the best, brightest, most talented people in the world—will converge on Stockholm to accept the honor. All except one. There will be a Bob Dylan-sized hole in the proceedings. It seems that Dylan, winner of the 2016 Nobel Prize in Literature, is going to be busy that day and can’t make it.

I’m not really sure what the Nobel Committee was expecting; you give an award to a guy who doesn’t really care about awards and then act offended when he doesn’t show up to accept the award? Those who know Dylan’s life and work are not surprised, though. He’s made a career out of being unpredictable. Just when you think you know him, Dylan has changed again.

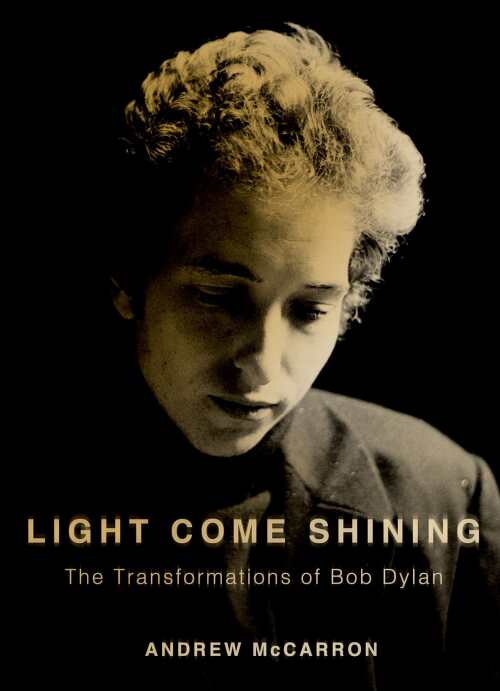

Andrew McCarron does not pretend to know just how Dylan’s mind works (doesn’t he have a lot of nerve to say he is Dylan’s friend?), but he has tracked the changes in the singer/songwriter/poet’s life. He put it all into a book called Light Come Shining: The Transformations of Bob Dylan (Oxford University Press). In our interview below, McCarron talks about what he calls Dylan’s “destiny script,” or his cycles of change. As for who really knows why he changes? The answer, my friend, is blowin’ in the wind.

Were you surprised at either Bob Dylan’s winning of the Nobel Prize or his perceived lack of immediate reaction to it?

Andrew McCarron: 'There are so many literary forms embedded in his lyrics.'

I was surprised that he received it and pleased. I’ve been teaching his lyrics as poetry for years now in the classroom and felt validated because certain colleagues and literary friends of mine whose sensibilities I respect have been dismissive of Dylan as a poet. I’ve always disagreed.

The Nobel Prize Committee was perceptive when it recognized Dylan’s importance as a sampler and promulgator of tradition. His musical identities have channeled the personae of a dustbowl Okie, a Beat poet, a Nashville songwriter, a Born Again holy roller, and a delta bluesman. Lyrics and melodies from the ’50s, ’40s, ’30s, and much earlier, flow through his albums.

And there are so many literary forms embedded in his lyrics: lyrical ballads, talking blues, jeremiads, sermons, elegies, dramatic monologues, and surrealist language experiments. Not to mention the fact that Dylan routinely appropriates themes and quotations from artists as varied as Henry Timrod, Muddy Waters, John Keats, and T.S. Eliot, keeping these writers circulating within public consciousness.

As for his lack of immediate response, that’s anybody’s guess. I gather that he’s an eccentric person accustomed to doing what he wants.

How do you find fresh material, or fresh perspective, to examine a life like Dylan’s, whose life has been examined by so many writers before?

The idea of writing something biographical about Dylan initially didn’t seem like a good idea, because, my goodness, there are so many good biographies out there. Whenever I looked online it seemed that another had just come out, or was about to come out. But then an approach came to me that felt fresh. I’d recently finished a PhD program in psychology in which I’d done work in an area called the study of lives. Some of the theory associated with this approach offered conceptual and methodological tools to help capture the shape of someone’s life by trying to represent it from the inside out. I decided to read through hundreds of pages of interview transcripts, Dylan’s own memoirs and lyrics in search of salient themes and narrative structures.

A lot of biographers take his self-explanations with a grain of salt because of his trickster quality. He has a reputation for shucking, jiving, and deflecting during interviews. But historical truth differs from psychological truth. Psychological truth is a little less concerned with whether or not you’re telling the truth, per se. It’s just as concerned with what you’re saying and why. It also requires looking for recurring stories, or scripts, which often contain the psychological fingerprint of a person. I immediately noticed the number of times Dylan cited a feeling of “personal destiny” to explain his changes. And in the instances of his most striking changes (e.g., the three taken up in the book), I discovered an underlying script. I call it the destiny script. So, my book is unique in that it privileges Dylan’s take on himself over outside interpretations of who he is and what he’s up to.

Reinvention has been the only constant thing in Dylan’s public life. Is this an image he wants to project, or does change define who he is?

Probably a little bit of both, but my book argues that he really has gone through mystical transfigurations. His reinventions aren’t merely the shenanigans of a wily performance artist. I argue that they are expressions of his innermost experience of self and identity. William James wrote about these sorts of changes in his chapter on conversion in The Varieties of Religious Experience (1902). And there have been more recent Psychologists who have studied the phenomenon as well, some of whom have referred to it as “quantum change.”

Many “quantum changers” claim that an unconscious force prompted their changes, which often came “out of nowhere,” and which remain challenging to explain. What’s more, these individuals frequently trace their transformational experiences back to specific turning points or scenes. My book claims that the same is true for Bob Dylan.

Do you think he’s laughing at writers who over-intellectualize his changing tastes?

Yes, I imagine that he is, or ought to be. Even if many of his reinventions are genuine, the amount of intellectual speculation and theorizing must be laughable from his perspective. In the book, I reference something Dylan said in an interview with Spin Magazine in 1985. Dylan was asked if there was anyone that he would enjoy interviewing himself. His response: Hank Williams, Apollinaire, Marilyn Monroe, John F. Kennedy, Joseph of Arimathea, Mohammad, and Paul the Apostle. He is then quoted saying, “I’d like to interview people who died leaving a great unsolved mess behind, who left people for ages to do nothing but speculate.”

What is your favorite Bob Dylan lyric?

I really like the line from “Not Dark Yet” (off of Time Out Of Mind from 1997) that goes, “I can’t even remember what it was I came here to get away from.” The words are hauntingly familiar; maybe it has something to do with the fact that who we become grows out of the crumbling remnants of who we’ve been. At its heart, that’s what my book is all about.

Howard Lovy is executive editor at Foreword Reviews. You can follow him on Twitter @Howard_Lovy

Howard Lovy