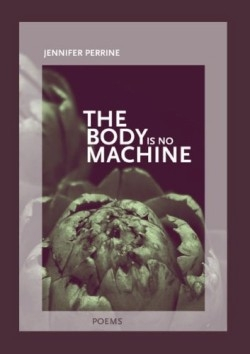

The Body is No Machine

Perrine’s titles say it all: “Gender Question #2: Butch, Femme, Androgynous, or All Over the Map?,” “In Honor of Your Birthday I’ve Been Mauled By a Dog,” “Menage a Trois with Two Women and an Imaginary Man,” and “Epithalamium with Peeping Tom.” From humor to sexuality, classic poetic forms to imagined encounters, Perrine’s poems, like the titles in her first book, titillate, surprise, and amuse—generally in the space of a few lines.

Perrine’s work has appeared in Green Mountain Review, Nimrod, and Southern Poetry Review, among other places. She teaches writing, gender studies, and Holocaust studies at Drake University. Perhaps her multiple interests account for the variety of subject matter in her poems. The book contains six sections. In the first, a dirt-eating mother appears, a cannibalistic fetus, and a dog-mauled daughter. Each poem engages the gullet, consumption, violence, but in the midst of the struggle, the words are graceful. In “My Mother Learns the Language of Poetry,” Perrine writes, “reproduction was nothing / less than an arabesque of cells duplicating.” In the second section, “The Night in Her Mouth,” the poems explore intimacy. In “Because You Have No Sense of Smell,” Perrine uses synesthesia to evoke scent for her lover, “your scent is the blue tinge rimming skim milk, // the rustle of barely opaque pages / in a Bible.”

In the third section, the poems take a turn, placing gender politics in the lyric poem, thereby making them personal. In “Portrait of D., After the First Operation,” she speaks to a friend who, in the process of becoming a “visible man” has had her breasts removed. Perrine writes “you’ve brought your scars outside: you, / wincing in the light, the air new, thick / as a hand under your unbuttoned shirt.” “Fiancee of Death,” the fourth section, looks closely at relationships and their failings. The poems are of broken or breaking people: a hated teacher soon to be murdered, a desperate woman on the side of a road, a drunk lover. “Love Song with Corset” renews the concrete poem, using the poem’s visual form to mimic the garment it figures.

The fifth section, “Clicks and Whirrs,” examines issues of the body from a brother’s amputated finger to the slow death of a parent. “The Shift of Dirt,” the final section, considers death. In its examination, all the themes that began the book find fruition in the end, particularly in the last poem, “In Praise of the Myclonic Jerk.” Perrine writes of the “pulse that calls me away / from desire, that speaks in its synchronous // voices: you are dying: you are waking.” Readers eager for the unusual and articulate lyric will read hungrily.

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.