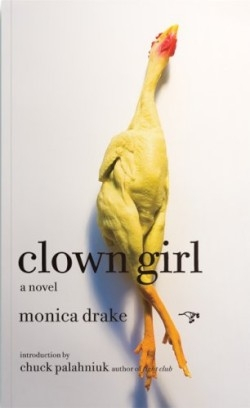

Clown Girl

Nita is a clown whose painted-on grin masks a world of sadness. The opening of Drake’s breathtaking debut finds Nita dressed as Sniffles the Clown, tying an endless stream of sheep and Virgin Mary balloons (Balloon Tying for Christ was the lowest-priced how-to book she could find) for a crowd of bratty, demanding children. But then a sudden “cardiac event” leaves her breathless and disoriented and she is escorted (by a dreamy cop named Jerrod) to the hospital—where she had been just weeks before after suffering a miscarriage.

The baby was the product of her relationship with fellow clown Rex, who is off seeking an audition for a prestigious clown college while she struggles to support him by performing at corporate events. Nita can’t get in touch with Rex, so he doesn’t know about the miscarriage. But Nita is accustomed to grieving solo, as the theme of loss has been a refrain throughout Nita’s life, starting with the death of both of her parents years earlier.

Released from the hospital with an uncertain diagnosis, the still-fragile Nita returns to her normal life—that is, if you can call any life in Baloneytown “normal.” She arrives home (a co-op where she lives with her ex-boyfriend, a drug dealer named Herman, and Herman’s new girlfriend) to find that her dog, Chance, has ingested some of Herman’s merchandise. And then the losses continue: Nita loses the lucky rubber chicken that Rex had given her early in their relationship, the funnel for urine collection given to her by the hospital (twenty-four hours worth of pee will aid in a more complete diagnosis), and her dog.

As Nita hits the town looking for her “missing Chance” (similar wordplay—that doesn’t pack a punch so much as land like a soft chuck on the chin—is sprinkled throughout the narrative, as when Nita refers to her poor life choices as “Rex-less behavior”), Jerrod the cop is in hot pursuit. He rescues her when she’s arrested for arson after an ill-fated attempt at juggling fire sticks. But even Jerrod can’t save her as her clowning gigs begin to veer from the lofty art she envisioned (a silent adaptation of Kafka’s The Metamorphosis is in the works) to prostitution-like performances catering to clown fetishists. And, just as Nita has lost so much in her life, she starts to lose herself: “The world was onstage. I was the lone audience slouched in the cheap seats. This wasn’t the clown I set out to be.”

Drake has written for The Oregonian and The Stranger, and has contributed pieces to the Threepenny Review and the Beloit Fiction Journal. Her story unfurls at a frenetic pace, mimicking Nita’s disorientation in her own crazy life. The tale is packed with pathos, as chortles of laughter and tears drip simultaneously out of the weird and wonderful story.

Reviewed by

Iris Blasi

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.